Struggle, Creation & Alienation

a more philosophical argument against AI and art commercialization, among other things

When I was in the 8th grade, specifically the latter semester of it, I got to take a class at the high school down the street from my middle school. I was a little late to my first day, where my teacher was reading from an article about what it takes to really be good at something. The specific wording has all but faded from my memory, however, the sentiment of it has rang true for the many years since I’ve taken that class. The gist: you have to love the struggle of it all. If you want to get fit, whatever that means for you, you have to learn to love working out. If you want to be in a healthy, happy relationship, you have to learn to love the highs and lows of communication and living a shared life. This teacher truly embodied this philosophy. My taking of this class was not at all standard; but I had gotten too accustomed to not being challenged, and so it was time for me to enter the “big leagues,” so to speak, with this math class. I thought I’d be normal fare. I failed my first test. Upon the returning of the test, my teacher admonished me that it was time to step it up. “You’re in an advanced high school class,” I remember her telling me. I was devastated, and a little offended, to be honest, that I wasn’t getting enough credit for being there in the first place. But in a way, she was right — if I wanted to be there, and actually embrace the challenge, I had to step it up.

I got an A in the class. But outside of the math I learned in that class (and boy did I learn a lot of it), that experience taught me so much more. I had to learn grit — persistence, tenacity, resilience. Even more, I had to learn a sort of stubbornness and what I daresay was a sort of ego, thinking that I just couldn’t let a class get the better of me. Those traits have served me, though their integration with my sense of self has been… complicated. The truth is, however, that I did have to learn to love the struggle.

You know what wouldn’t have gotten me all of those benefits? Cheating my way through the class. I probably could have learned how to, I’m sure others did. And in a strict sense, it would’ve been a useful skill for me to learn. But really, that isn’t something that just meshes with the way I move through the world.

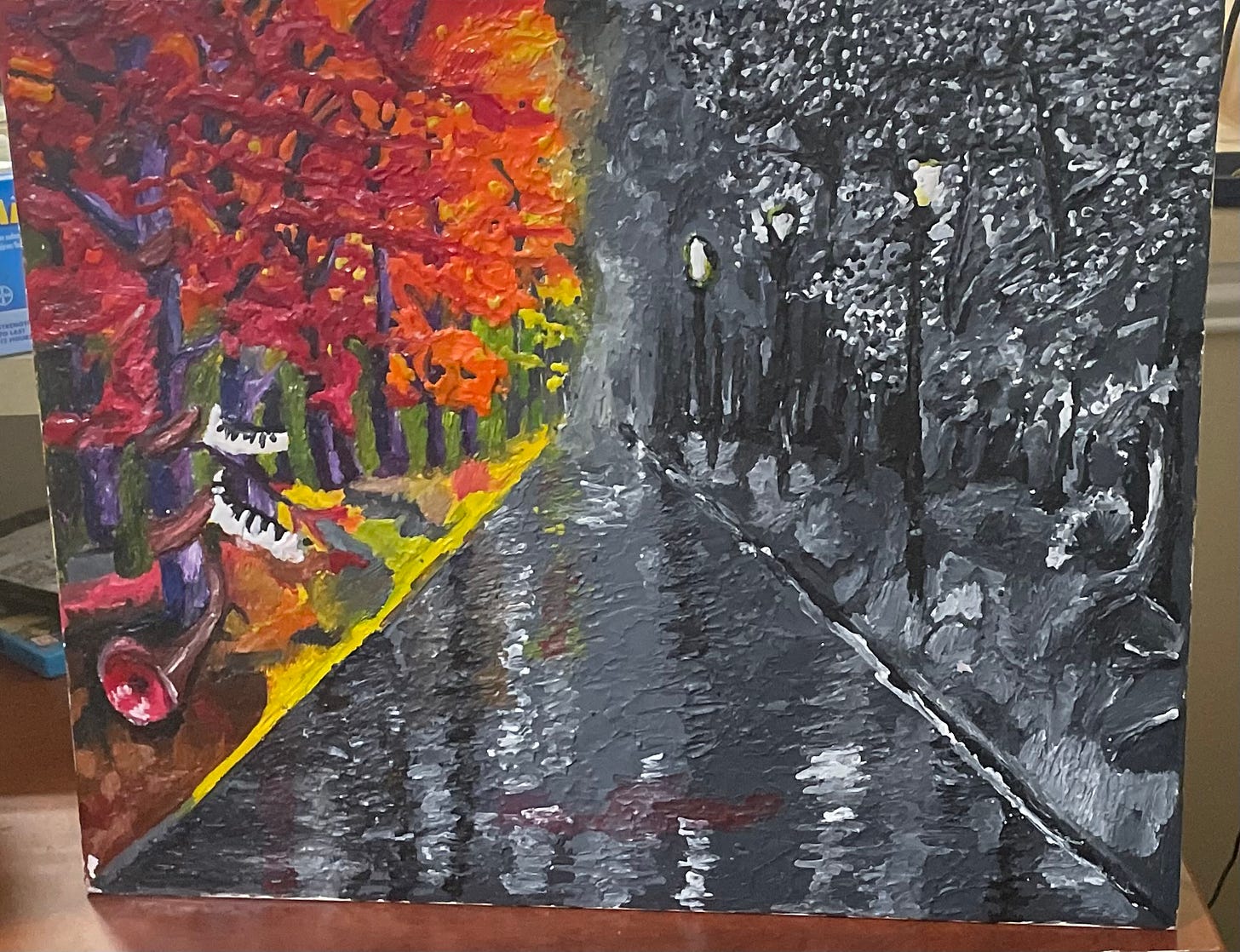

There is something of an obsession in me in everything I do. I throw my all behind what I do, I have to engage deeply, I have to, often, struggle. This is, I believe, linked to a perfectionistic sort of maximalism that actually tends to prevent me from doing things, but I don’t think it’s interfering to the extent that it could be. For example, I love drawing, an interest I discovered in the latter half of my high school years. We had weekly “word drawings” that we had to do, and I often just wasn’t content with phoning it in, to the extent that I would procrastinate on them to no end, especially when we had some really interesting projects going on at the same time. But when I did get around to doing them, I was usually proud of them! I could critique them to no end, but I could rest in the fact that I did pour myself into even those inconsequential weekly drawings. And that meticulousness, I believe, is what really drove me to go big on the projects I did in my two years of art in high school:

It’s a little wobbly on some edges, but honestly, I still look upon this with incredible fondness and pride. I spent a month on this, holding a hot glue gun to crayons for hours at a time, scratching entire sections of wax off my canvas to get it right ,and you know what, it turned out pretty damn good, if I do say so myself. And the reason it did is because I fought for it!

I think my creative and intellectual passion is one of the traits that forms the core matrix of my personality — if you were to strip everything from me, you’d see a burning flame just has to learn and make shit, and I think that other people, mentors that is, recognizing that is what has gotten me the success I’ve had thus far.

At the intersection of learning and making, of course, is learning how to make, and as I learn the ins and outs of all my interests and hobbies, I gain an immense respect for any and all who try their hand at the act of creation, and a deep sense of reverence for those who master their craft. Because what you learn, when making, is that to make is to struggle with the medium. That to make a painting is to mix colors again and again and again, being willing to scrape it up if it isn’t good enough. To write a good essay is to think and think and rewrite and rewrite until each sentence is crisp and clear and conveys a logical set of ideas. That to code is to test and debug and read documentation until your code reflects an understanding of how and why it should work, and what it’s working with. That to make is to fight.

This point is subtle, but deeply important, and so I’m going to say it again. Making things that resonate, that reflect beauty and effort, is to struggle with the process of making. Every movie that’s brought you to tears, was shot and edited. You paint a canvas with your nose right to it. And of course, you have to zoom out in order to get that emotional vivacity, to see what you’re doing it all for, to represent the animus of your work, but the doing is so much closer, and I think that that’s what we really respect about the greats. Michelangelo’s work on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is breathtaking not only because of its vivid hues and display of divinity, but because we know that Michelangelo stayed on his back for actual years to make it. That he had a relentless fire that sought to engage with his work to perfection. It’s respect as much as it is awe.

The two elements of a good creation, that emotional soul and physical struggle, they operate synergistically. An emotionally resonant work often requires engagement, and it’s soul that motivates the struggle towards something great1. It’s the same with learning. To internalize something, to learn it, is to struggle with it, until the abstract idea of it becomes something ingrained into your very being. That is not a process that you can take for granted.

And so it becomes clear, to me at least, why AI as a replacement for creation and learning is insidious, if not outright despicable. Sure AI can be useful. For example, writing certain bits of code with AI can just make the process overall faster, and is akin to a power saw, simply another constituent of experienced’s toolbelt.

When you want to make something, however, from start to finish, something that means something, you can’t just phone it in. That’s not what creation is. You’ve bypassed the part that imbues it with human soul — the struggle. And even more, where’s your flame? That game you wanted to make, where’s the fight to bring it into existence? Why would you let a homogenizing, stochastic, inherently generic next token predictor do something as meaningful to the human experience as make art? Your brain, that’s a treasure! Your body, that’s the vessel with which you move through the world during your limited time on it. And indeed that time is limited — but what time are you gaining, really, by short-changing yourself of the process of making, of learning? Don’t have AI generate that essay for you, you really are better than that!

And sure, maybe you don’t believe in the worth of an assignment, and indeed there’s something to be said about how the education system (and work!) often leave us with tedium, but really, why does it have to be viewed as tedious? This is what I’m talking about, with my internal fire, being an asset that allows me to frame even what are easily regarded as insipid assignments as something worth doing. I will put my all into that essay, as little bearing it has on my grade, because I refuse to put garbage out into the world.2

And really, I think society’s ready acceptance of AI is reflective of a bigger issue. It seems like we’re dealing a new dearth of meaning. Everyone comments on how mass media art, like the average Marvel movie or commercial pop artist, just seem to lack soul. And I… have complicated opinions on this! Because actually, I think there is soul to be found in the processes of many of these productions. The VFX artists, for example, on those Marvel movies, as overworked as they are, are really trying to create! And there’s something to that, I believe. Now, there is an immense potential for the lack of vision in these, and of course that means that at least half of the artistic question is lacking, but that’s often subjective. The labor, however, is objective, and I think that even the sloppiest Disney remake still has pockets of merit that deserve to be held in mind.3 But that’s the softie in me.

But of course, these companies (and perhaps some artists, but I become much more skeptical of this perspective when it comes to individuals) don’t believe that they need to have vision to make money, they just need to rely on enough people putting the effort in to make something worth doing. And that belief permeates individuals, too, though in the opposite way.

Take your average student, for example, and you will (because of years of conditioning) find someone who wants to maximize their chances of an A, or whatever grade they deem good enough, and do exactly enough along that path. And I do think I have things to learn from them, about being willing to let go, because often it isn’t that deep, and sometimes it’s just time to phone it in. But sometimes I get equal parts frustrated and saddened by that mentality. Because there really is a lot of joy to be found even in the mundanities, I think. There’s a joy in just learning something, or crafting an essay that you a take pride in, or any manner of struggles. But pride and joy don’t necessarily correlate with grades4, and sometimes priorities need to be made.

This is the point in the essay where I have to make an obligate connetction to capitalism. (I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I can’t help it.) There’s this concept of alienation, that philosophers Marx, Nietzsche, and Heidegger speak of in different ways. Marx and Heidegger speak of it a more laborial sense; our souls are encouraged to be oriented to fruitless, meaning-stripped labor, and not any sort of meaningful work. In fact, we are often encouraged away from such things, as the things that make us fulfilled and happy are often not the same as the ones that generate revenue. So, naturally, we prioritize getting done quicker over better, as we alienate ourselves from the meaning of our work.

But Nietzsche also has a perspective that’s worth investigating here. With the shattering of Christian ideals as the dominant and surefire source of morality, we find ourselves adrift in a universe void of inherent meaning. We become alienated from the world around us, falling into nihilism. But Nietzsche posits that we all have the power to create our own meaning, in the project of making ourselves into what he calls the Ubermensch (literally, “super man,”), which I am going to ham-handedly rephrase as participating in the act of self-betterment. The way he suggests? Struggle. Struggle5, when towards the end of something noble as creation, is the method of becoming an Ubermensch.

So from the lens of economic and philosophical alienation, it makes perfect sense why AI and corporate “slop,” as some call it, are so readily accepted and consumed, respectively. They respectively represent a resigning from the act of creation, and the act of mindful consumption, for the purposes of bypassing struggle and economic gain, also respectively.

The real power in the concept of alienation is that is strictly personal. You can fight alienation in your life by choosing to consume mindfully, to reject mindless productivity, in favor of creation, in favor of struggle, not just for the purpose of creating a product, but for the purpose of creation itself. It is finding meaning in making things with which we imbue our soul, that restores our soul in the face of a system which would destroy and extract it if it got even a cent extra more of “productivity,” or profit. But you don’t have to do that!

You too can light the fire of creation, of love, of passion, inside yourself. But you have to love the struggle of it.

This is why I wholeheartedly believe in and support the Rothko’s of the world. That flat red painting took time and effort to make as smooth as you’re viewing it. That is not just a lazy work meant to let postmodernism give it meaning (not that I often view experimental art as lazy, but I know many can), that is pure struggle.

It must be recognized that this is coming from a unique, and privileged, position. I get to do things I derive a lot of meaning from, and not everyone gets to do what they get meaning from. And that privilege honestly is distributed in very interesting ways, not necessarily along the usual lines (though of course that can make it more likely).

What you will find is that aside from the creative flame, the other half of my identity matrix is an occasionally infuriating dedication to seeing beauty and positivity in things (and people!)

Though, in my experience, they do. But that could be a chicken, egg, sort of dilemma, because I’m wired to place effort towards things I believe in. I’m just lucky enough to believe in a lot of things.

I should take the time to say that struggle is not a good in and of itself! That mentality creates all sorts of problems.